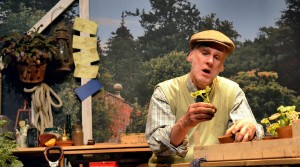

PMac Productions presents a delightfully tactile version of Alfred Shaughnessy’s adaptation of Reginald Arkell’s 1950 novel Old Herbaceous, carefully cultivated in a raised-bed greenhouse in which Herbert Pinnegar (Peter Macqueen) reminisces on vignette memories of people he’s met, kept alive through his love of gardening; the remarkable, the formidable and the enchanting.

“Anyone who loved to garden could always walk straight into my soul.”

Pottering amongst the seeds and cuttings in the York Theatre Royal Studio, Macqueen is a master storyteller, captivating the audience from the off with his twilight-year Bert full of light, laughter and fondness for the bygone era from which he grew. Recounting his journey from turn-of-the-century orphan boy to head gardener to esteemed flower show judge, Old Herbaceous lays forth his friendship with the lady of the house, Mrs Charteris, his brief early tease with romance, and an undertone of a futility complex tied into the war he is not fit to serve in. How does one fill one’s time, and feel valuable, when left back on the home front? Macqueen’s warm, welcoming demeanour and comforting South-Western rural accent and sensibility (“Wurrrr…”) immediately draws you in, making the pathos of his background frustrations all the more affecting.

Bookended by birdsong and clock chimes, and sown with seeds of gardening wisdom, this one-man show is a humorous portrayal of a single-minded yet gentle man with a passion for plants. Orange Fizz scented geranium is passed around the studio, ceramic pots are scrubbed clean, watering can spray strays a little onto a tickled front row (an accident, of course…), fresh orange is munched and immediately put to pasture as a resourceful slug trap (“Can’t swim, see”, he says as he demonstrates a breaststroke, cackling softly), seed trays are sifted and cuttings re-potted. These little touches perfectly garnish an enjoyable, moving show. Macqueen’s facial ticks and habitual gestures round off his character artfully.

“Funny thing, how gardens change over the years…”

Rooted in an era at so much friction with our own, there are some moments that don’t date well; namely Pinnager’s slut- and fat-shaming spin on his encounters with certain characters, which fall uneasily with younger members of the audience while older generations find them uncomplicatedly amusing. “I’m as good as the next man to be wheedled by some comely young wench.” Here is a man very much alive and alert and participating in his surroundings – he plans small surprises, writes letters to Kew Gardens – but in his position of privilege as a working class white man, he “scores a victory for tradition” when he sides with safety on fixing something old if you like it enough, rather than progressing into new territory. This feels emblematic of a wealth of people in his ring of society enabling change to be held at bay. His inevitably internalised elitist aspirations send home a sad reflection of how a working majority can be lead to prioritise the maintenance of a segregated capitalist nation’s status quo over honouring their own identity as worthy in its own right. Bert is concerned with knowing one’s place, acting one’s age – symptoms of an efficiently oppressed time.

If you don’t pay attention, you’ll get lost among the narratives – the montage of past relationships comes thick and fast, and not all characters are completely discernible, through no fault of Macqueen’s. The sudden violence of the master-of-the-house’s death is jarring, owing to us having little experience of the master himself, though we feel the weight of it via Madam’s tragic withdrawal. The transformation from chuckles to poignancy is quite startling; Macqueen’s ability to switch to Bert’s nervous inarticulacy is perhaps even underused. As the lighting dims to dusk, the fraught wondering if you’ve made a mark on someone’s life is palpable.

“Remarkable man.”

Find more on Old Herbaceous, and MacQueen’s other works, here.