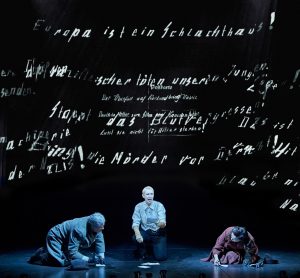

Denis Conway, Jessica Walker and Charlotte Emmerson in Alone in Berlin; Photo by Manuel Harlan

Charlotte Emmerson (Therese Raquin, The Duchess of Malfi), Denis Conway (The Wind That Shakes the Barley, Brooklyn) and Joseph Marcell (King Lear, The Fresh Prince of Bel Air) lead a small ensemble cast directed by James Dacre, Artistic Director of Royal & Derngate Northampton, in the world premiere production of Alone in Berlin, Hans Fallada’s acclaimed novel translated and adapted for the stage by Alistair Beaton; a York Theatre Royal and Royal & Derngate Northampton co-production, in association with Oxford Playhouse.

The cast also includes Abiola Ogunbiyi (Jamestown, Girls, The Book of Mormon), Jay Taylor (Nell Gwynn, Wolf Hall), Julius D’Silva (The Crown, The Producers) and regular Complicite Theatre Company collaborator Clive Mendus.

Set in 1940, the play is a gripping portrait of life in wartime Berlin and a vividly theatrical study of how paranoia can warp a society gripped by the fear of the night-time knock on the door. Based on true events, Alone in Berlin follows a quietly determined couple who stand up to the brutal reality of the Nazi regime. With the smallest of acts, they defy Hitler’s rule – facing the gravest of consequences.

Described as “the greatest book ever written about German resistance to the Nazis” by Primo Levi, book sales for Alone in Berlin entered the bestseller list again three years ago – almost unheard of for a twentieth-century literary classic – as its themes began to resonate across the world once more. Regularly adapted for stage productions across Europe, this is the first time Fallada’s masterpiece has been seen on a British stage.

The production is designed by three-time Tony nominee Jonathan Fensom with lighting design by UK Theatre Award winner Charles Balfour, video design by Nina Dunn (Plenty, Copenhagen and Fiddler on the Roof, Chichester Festival Theatre), featuring illustrations by Jason Lutes from his epic graphic novel Berlin, and songs by Orlando Gough performed by cabaret singer Jessica Walker. A visual composition like a wall of sound, the stage is used in every inch with Sütterlin script projections, angular protrusions and lithe moving pieces that overlay to create an impressive brutalist depth.

The weight of Fallada’s own parallel difficult and complex experience living under the Nazi regime is deeply felt in Otto’s lost sense of political alliance and ownership of his identity; Conway maintaining a subdued character unsure of where to put his energy if not into the machine, alongside Emmerson’s calmly resolute Anna who simply takes what support she can get from her husband. Calling out the cowardice in his commitment to obedience and being a ‘model citizen’, her decision not to dwell on his motivations is perhaps his biggest motivator to join the resistance after all. Otto’s final speeches are a reckoning with his ignorant hesitance and impotent efforts; a deflated acknowledgement of a life barely lived, a task barely begun.

The pace and tone of the couple’s efforts in this production are fittingly mundane, showcasing the small, everyday actions of their historical inspiration, the Hampels. Even their reaction to the death of their son is underplayed; is spoken of so matter-of-factly that you could blink and miss the entire point of galvanisation in this couple’s turn towards the movement. Ogunbiyi is similarly reined in to portray a steadfastly level Trudi, who appears no different when she hears of her lover’s death to when she is rescuing a vulnerable older woman from the Nazis or when she has relinquished her outspoken allyship for the sake of a comfortable life.

Allowing the Quangels space to come to arms, and thought, in their own time, the show places the Nazi and supporter contingents in direct juxtaposition with full bluster, firing on all cylinders and achieving nothing fast. The acting is top notch across the board, but interestingly, the most engaging character portrayals come in the sidelines. D’Silva’s overbearing Klaus Borkhausen and Mendus’ Benno Kluge bring so much to the table in their dialogue and energy above the dulled prose of the rest, spotlighting the danger of confidently-asserted self-preserving default centrism. It introduces the idea that maybe these men are so self-assured because they’re not doing the intellectual labour of those who appear less sure. The levelling of these complex emotional extremes hints at Fallada’s possible mental state in revisiting his painful past when telling the Hampels’ story.

Walker’s operatic narrator, ‘Golden Elsie’ (borne of Goldelse, though here more akin to Cabaret’s M.C.), adds a strange layer of remove to the starkly stunning aesthetic framing, calling on Brechtian Epic Theatre techniques to proffer characters’ motivations and explain situations with such simplified, repetitive phrases and stylised presentation, always permeating the action, that despite her likely personification of an angel of death, it distracts from the personal elements of the story and reminds you consistently of the oppressive omnipresence of the state. The decision to disengage with the story’s subjects does undercut its impact, though the visuals are no less than breathtaking – particularly in their blinding punctuation of the play’s open and close. Overall, this makes for a commanding, fascinating piece of theatre, and its pertinence cannot be ignored in a time when the world spirals towards another fascist uprising, enabled by bluster and inaction.

Alone in Berlin is playing at York Theatre Royal until Saturday 21 March, tickets available here.